Weapon to Spot Fake Drugs Earns Saint Mary’s First Patent

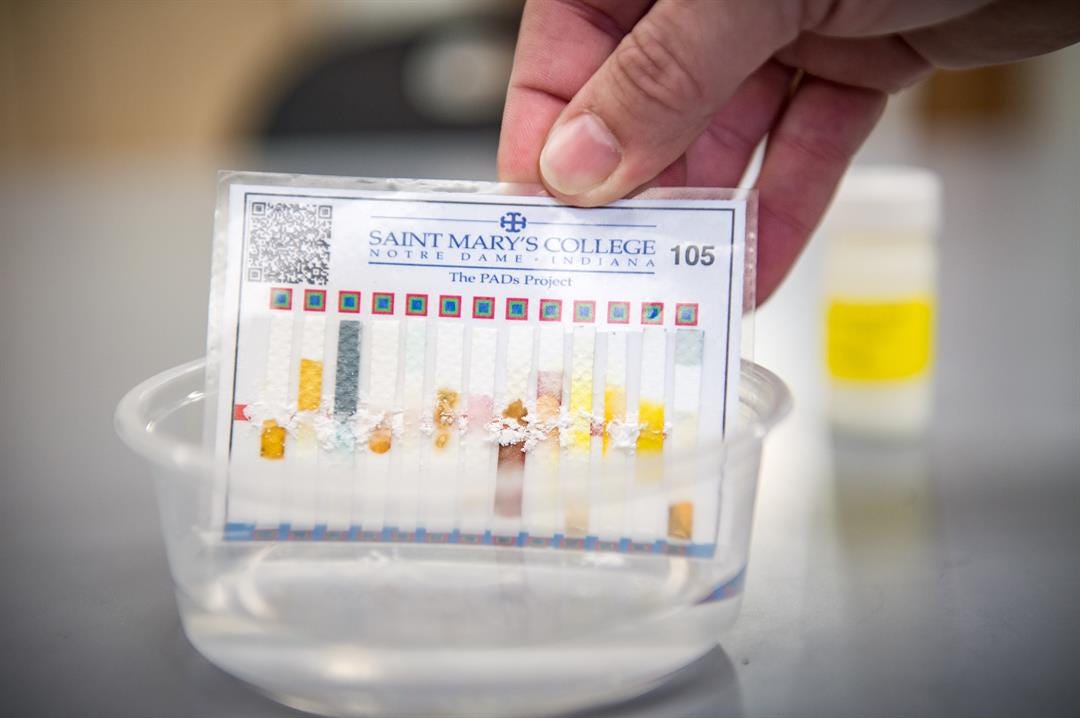

The user scrapes a pill across the card and dips it in tap water.

The user scrapes a pill across the card and dips it in tap water.

Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen you take a medication, it’s doubtful you question its authenticity; agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulate the pharmaceutical industry to ensure drugs are what their developers claim them to be. Developing countries, however, lack such checks and balances, meaning patients can more easily fall victim to fake or counterfeit medications. Researchers at Saint Mary’s College and the University of Notre Dame have developed a simple test card—about the size of a credit card—that can verify an authentic drug, or red flag a counterfeit one, with one simple swipe of a suspicious pill. Groundbreaking in more than one way, the technology also marks Saint Mary’s first patent.

Saint Mary’s Professor of Chemistry and Physics Dr. Toni Barstis says her students pushed her to pursue the patent, which now serves as validation; she believes many underestimated the scientific might of the small, women’s liberal arts college.

“I’ve gotten some kind of snotty comments from businessmen and women who didn’t expect a small college to do this kind of research; we weren’t viewed as an academic institution where real, authentic, genuine research was being done,” says Barstis. “Even though they’re at a small institution, our students—who are women—are doing excellent work. And it has nothing to do with gender; it has everything to do with their intellect and abilities.”

In addition to being the school’s first patent, it’s also the first for Barstis personally and the project’s collaborator, Notre Dame Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Dr. Marya Lieberman. The product, called Paper Analytical Device (PAD), is a small card that could be a very powerful weapon in developing countries.

The user simply scrapes a pill across the card—a chemically-treated piece of paper that costs only a few cents to make—and dips the card in tap water. Within minutes, color changes on various test regions loaded with dry chemical reagents verify authentic ingredients and alert the person to fillers commonly used in fakes.

“If you’re in a developing country, and you’re not given the full dosage of the active pharmaceutical ingredient, you’re not going to get better,” says Barstis.

Counterfeiters may also substitute the active ingredient with “fillers”; Barstis says these can be as benign as starch, or as dangerous as road paint or dirt that’s contaminated with heavy metals, such as lead.

The World Health Organization estimates about 10 to 30 percent of drugs in developing countries are “substandard or falsified.” The National Institutes of Health found 35 percent of 2,300 malaria drug samples tested in sub-Saharan Africa were low-quality—either fake, expired or poorly made—which could unravel years of progress in the battle against the disease. Barstis cautions such statistics underestimate the true scope of the problem, due to under-reporting.

“Internet pharmaceuticals can be as high as 80 percent [that are counterfeit],” says Barstis. “It’s a serious issue. As more and more people are looking toward the Internet, this could be a problem in the U.S.”

PADs can be modified for various medicines, and Barstis says the research team is open to licensing the technology to a company that can manufacture the pads. She believes a card could be produced for less than 25 cents; the current “gold-standard” method costs hundreds of dollars.

Just days after receiving the patent, the team earned a $200,000 grant from the National Science Foundation for Saint Mary’s and Notre Dame students to evaluate pharmaceuticals and water using PADs on-site in Nepal and Kenya. Beginning with the development of the technology, and soon utilizing it in developing countries, Barstis says the students have been motivated by the Catholic schools’ missions “to do good.”

“The students want to make a difference and apply their skills to a wider audience—that’s the dream for many of them,” says Barstis. “They’re dedicated to scientifically, and humanitarianly, making the world a better place.”

Barstis describes some of the risks associated with substituted ingredients in counterfeit pharmaceuticals.

Barstis says the PADs’ end user varies depending on geographic location.

Lieberman says the patent helps get the technology “out of the lab and into the world.”